On Battlecruisers

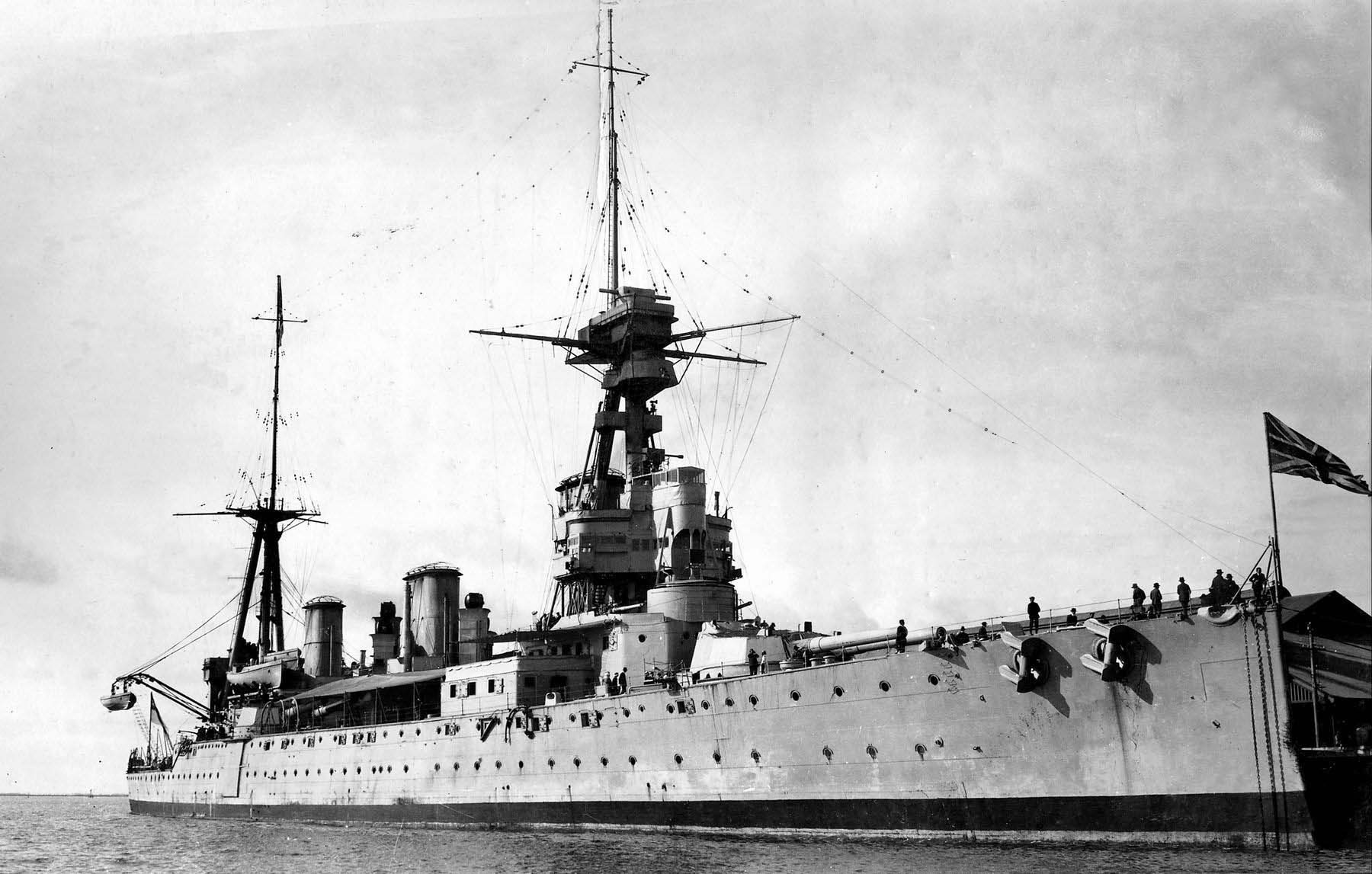

The battlecruiser Hood. Sleek, swift, and beautiful, she was the pride of the Royal Navy in the interwar period.

The battlecruiser Hood. Sleek, swift, and beautiful, she was the pride of the Royal Navy in the interwar period.

Today, I’d like to discuss a type of warship surrounded with controversy: the battlecruiser. The British Royal Navy (RN) lost three of these majestic warships at the Battle of Jutland in 1916: The Indefatigable, Queen Mary, and Invincible (with Rear Admiral Horace Hood aboard) all blew up with almost no survivors. Years later, in 1941, the HMS Hood, Britain’s last and most advanced battlecruiser, was lost in the Battle of the Denmark Strait–exploding just as violently as her predecessors sunk at Jutland.1 Something was evidently wrong with these “bloody” ships.2

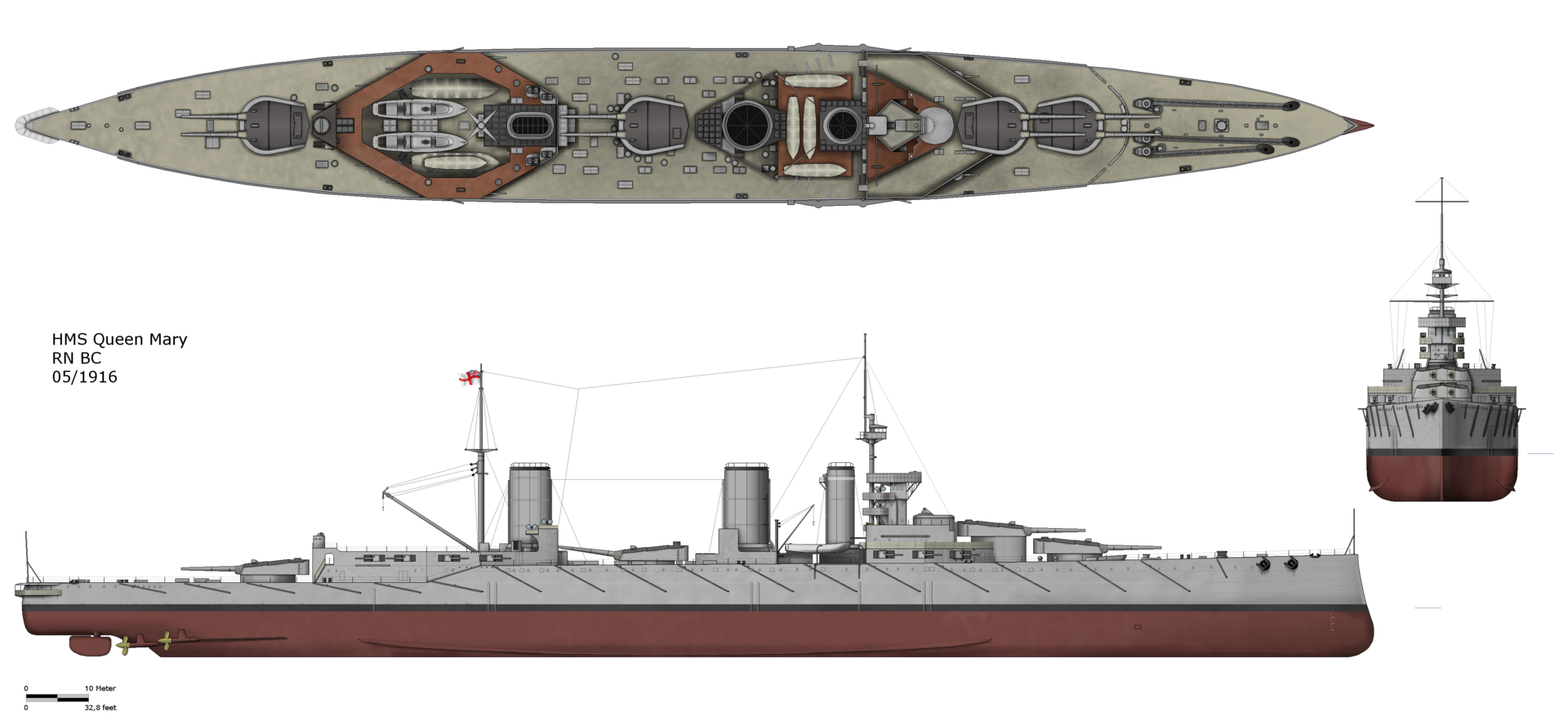

The battlecruiser Queen Mary, sunk at the Battle of Jutland in 1916.

The battlecruiser Queen Mary, sunk at the Battle of Jutland in 1916.

Many have concluded that the loss of these four vessels irrefutably demonstrated that the concept of the battlecruiser was unsound. As I see it, this is a misleading conclusion–the heavy losses sustained by the British at Jutland can much more accurately be attributed to the manner in which the ships were deployed and handled, rather than to any inherent flaws in the designs.3 Nonetheless, the battlecruiser, with the armor of a cruiser but the guns and engines of a dreadnought battleship, was inherently unfit to serve in the line of battle, and the concept that these vessels could join into the line of battle after spotting the enemy fleet and reporting its position to the main body of their force was, without a doubt, problematic. But, without going into too much detail, allow me to pose a different argument, that the battlecruiser was an ideal warship for the protection of British commerce across the globe–that there was no financially better option. In British Battlecruiser vs. German Battlecruiser, published by Osprey in 2013, naval historian Mark Stille argues that the capital required for the British to procure a single battlecruiser could have been much better spent on a larger number of smaller cruisers.4 While he may be right, I would like to provide a different perspective.

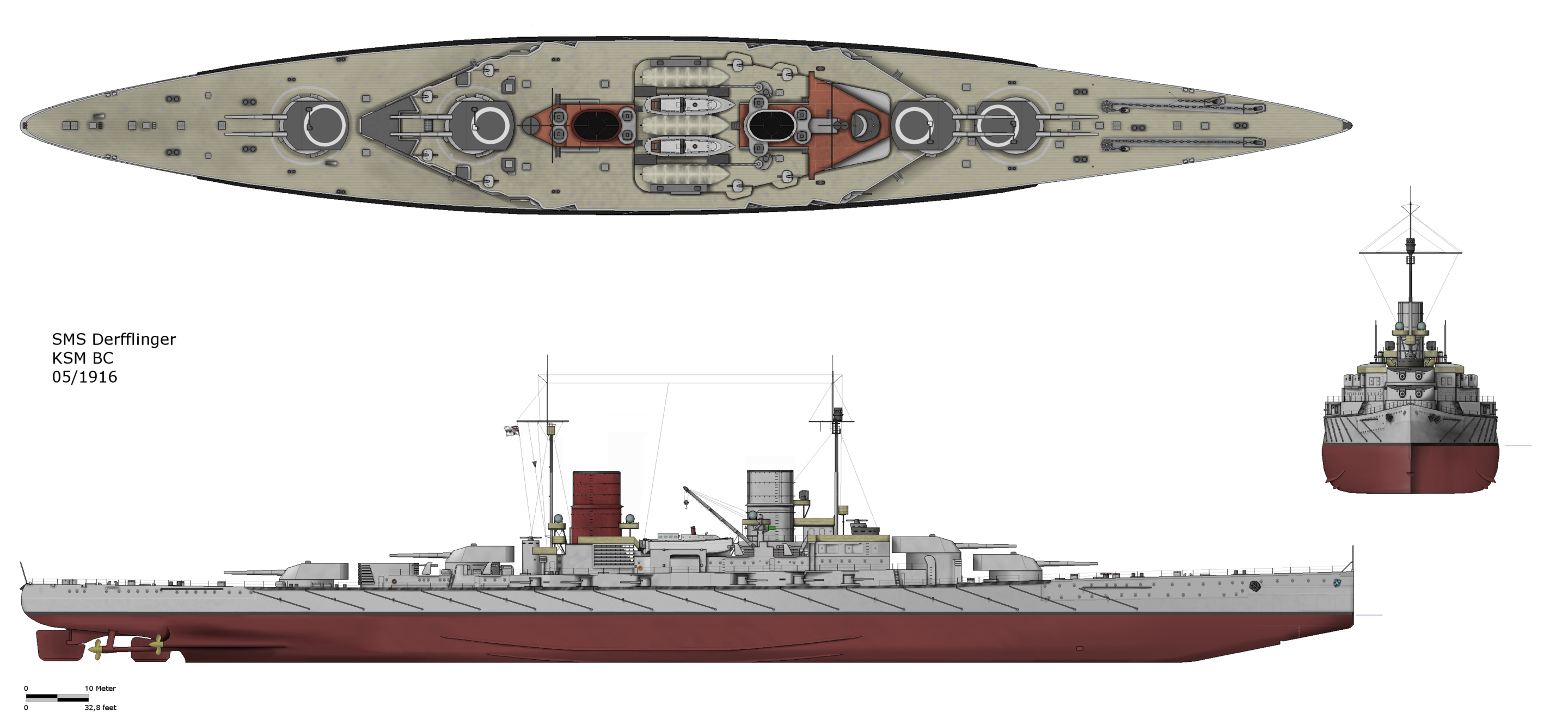

A drawing of the German battlecruiser Derfflinger. Capable of speeds in excess of 25 knots, the Derfflinger class nonetheless had an armored belt reaching a maximum thickness of 12 inches (compared to 9 inches on the most advanced RN battlecruisers Lion, Princess Royal, Queen Mary and Tiger) and an armament of eight 12in/50 guns. As stated by Stille, “These were arguably the best battlecruisers to see action during the war and came closest to being fast battleships” (Stille 42).

A drawing of the German battlecruiser Derfflinger. Capable of speeds in excess of 25 knots, the Derfflinger class nonetheless had an armored belt reaching a maximum thickness of 12 inches (compared to 9 inches on the most advanced RN battlecruisers Lion, Princess Royal, Queen Mary and Tiger) and an armament of eight 12in/50 guns. As stated by Stille, “These were arguably the best battlecruisers to see action during the war and came closest to being fast battleships” (Stille 42).

At the end of the 19th century, the Royal Navy’s numerical and qualitative superiority was unquestionable; the French, realizing they could never defeat the British in a major fleet engagement, decided to invest in the construction of a large number of armored cruisers which, in the event of war with Great Britain, could harass British commerce across the globe, crippling their economy. However, with the advent of the steam turbine, the age of the armored cruiser was coming to an end–it was now possible (albeit at great expense) to build a ship with the speed of a cruiser and the armament of a dreadnought battleship, although armor would have to be sacrificed in order to conserve weight. This class, the battlecruiser, would theoretically be able to outgun anything it couldn’t outrun (although as stated previously, this makes little sense in a line of battle or against other battlecruisers), and rendered all armored cruisers obsolete; the ability of the battlecruiser to intercept and destroy armored cruisers was amply demonstrated when Invincible and Inflexible sank Scharnhorst and Gneisenau at the Falklands in 1914. No standard cruiser could have performed the task as well.

Indefatigable class battlecruiser New Zealand, present at Jutland.

Indefatigable class battlecruiser New Zealand, present at Jutland.

So, was the battlecruiser concept a sound one, and were they worth the investment? Yes, and no. The battlecruiser was extremely effective at destroying enemy cruisers, and while used in this role would only be put at serious risk if used in battle against another vessel of its type; with this in mind, which other nations besides for Germany and the United States could actually afford to build and operate a sizeable fleet of battlecruisers? Although much has been written on the superiority of German battlecruisers to their British counterparts, and these German vessels proved quite useful in the major fleet actions of the war (Dogger Bank, Jutland), there was little or nothing they could do to prevent the British battlecruisers from operating with impunity across the globe, for they could not sail around the English Isles or through the English Channel into the North Sea without risking interception and annihilation by the Grand Fleet under Admiral Jellicoe. Thus, I would posit that the battlecruiser was, in many ways, quite a useful asset and arguably even an ideal instrument of seapower for the British Royal Navy prior to and during the First World War.

A photo of Derfflinger.

A photo of Derfflinger.

Unless otherwise stated, no images on this site are my own.

Copyright © feargodanddreadnought.com. All rights reserved.

Select Bibliography:

Hill, Richard. War at Sea in the Ironclad Age. General editor John Keegan. London: Cassell & Co, 2002.

Massie, Robert. Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany, and the Winning of the Great War at Sea. London and New York: Random House, 2003.

Stille, Mark. British Battlecruiser vs. German Battlecruiser: 1914-1916. Oxford: Osprey, 2013.

References:

-

While the circumstances of Hood’s sinking were quite different from those of the battlecruisers at Jutland (and she was better protected), I am of the opinion that her destruction by the German battleship Bismarck has hammered into societal consciousnessnes the notion that the idea of the battlecruiser was entirely unsound and that these ships were all liable to catastrophically blow up due to their lighter protection. ↩

-

Following the catastrophic explosions of Indefatigable and Queen Mary at Jutland, Vice Admiral David Beatty, in command of the Royal Navy’s battlecruisers, was told by a signalman on his flagship Lion that the battlecruiser Princess Royal had also blown up (which turned out not to be true). With incredible coolness in the midst of such a heated action, Beatty stated that “there seems to be something wrong with our bloody ships today” (Massie, 596). ↩

-

As described by historian Robert K. Massie in Castles of Steel: Britain,Germany, and the Winning of the Great War at Sea, “No one in Britain or Germany had realized the menace of an explosive flash fire within an enclosed gun-turret system. In Lion, Seydlitz, and their sisters in both fleets, shells and powder journeyed upward on hoists from the magazines, through the turret lobbies, and into the turrets to the breeches of the guns. These separate compartments remained open and unsealed. A flash fire at any point along this extended route could spread quickly to all other points, including the magazines. Such a fire had occurred in Lion at the Dogger Bank and might easily have destroyed her. The fire in her A turret lobby, which caused most of her casualties, could have spread downward into her ammunition handling rooms and from there into her magazines, where a cataclysmic explosion would have destroyed the ship. Fortunately, little ammunition was present in the turret lobby and the resulting fire was small and rapidly extinguished. As a result of this escape, the intrinsic danger of fire transmission went unrecognized on board the ship and at the Admiralty and no effort was made to install antiflash devices in turret trunks to prevent flames from spreading. Not until after Jutland sixteen months later, when the battlecruisers Queen Mary, Invincible, and Indefatigable blew up from this cause, were these corrections made in British ships” (Massie 419). ↩

-

As written by Stille, “The question remains—was the battlecruiser effective? To answer this, the missions of the battlecruiser need to be kept in mind. These can be boiled down to protecting trade and acting as the main scouts for the battle fleet. In reality, these missions could have been carried out by an armoured cruiser with a standard 9.2 inch armament. Fisher’s demand for an all-big-gun ship with high speed was flawed from the start, since once assigned to the battle fleet as a scout, it would inevitably be used as any other capital ship. Once employed in such a manner, its lighter scale of protection was bound to jeaopardize its survival. It also must be pointed out that battlecruisers were much more expensive to build than battleships and had increased demands for machinery” (Stille, 76). ↩